Neolithic and Bronze Age Agriculture Experiment at Butser Ancient Farm

In our latest blog, archaeobotanist and current PhD student at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology, Anna den Hollander, explains recent experiments in crop planting and processing taking place over the summer here at Butser.

In our latest blog, archaeobotanist and current PhD student at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology, Anna den Hollander, explains recent experiments in crop planting and processing taking place over the summer here at Butser.

Our current Agriculture Experiment at Butser Ancient Farm has a dual aim: first, to understand microwear on lithic tools used in the harvest of crops and second, to get experimental evidence for the kind of weed assemblages favoured by different harvesting methods. The project is being carried out here at Butser Ancient farm, where a Late Neolithic/Bronze Age pasture has been recreated growing spring spelt (Triticum spelta sp.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare sp.) – two grains that were once the main staples in Europe but are hardly used today. The seeds were kindly provided to us by the National Institute of Agricultural Botany (NIAB) and Dove’s farm. They were sown on the 15th of April of this year. The field is currently flourishing, and we are looking forward to harvest the crops at the end of July/beginning of August depending on their growth.

The study of lithic microwear, carried out in this experiment by Dr. Ivana Jovanović in collaboration with Prof. Ulrike Sommer (UCL), is a technique primarily used to understand stone tool function, allowing researchers to identify past behaviours through microscopic traces left on lithic material culture. The original microwear study was done at Butser Ancient Farm by Peter Reynolds, Butler’s first director, so 50 years after the founding of Butser it is great to be expanding on this early work. By using handmade replicas of Neolithic/Bronze Age lithic harvesting tools to reap the spelt and barley crops, and studying the traces of the silica in the stems, we hope to create more accurate reference material to identify similar use wear on archaeological lithic blades. Similar studies have been caried out for Near Eastern Neolithic and Epipaleolithic contexts, but Bronze Age microwear remains understudied especially in grasses such as spelt. Analysis will be carried out at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology in collaboration with Dr. Michael Charlton.

Figure 1 & 2: (1, left) Dr. Ivana Jovanović sowing spelt at Butser farm, 15 April 2023 (2, right) Anna den Hollander identifying weeds in the field of barley, 16 June 2023. Photo: Anna den Hollander and Ulrike Sommer.

The study of weeds in association with agricultural practices is one of the cornerstones of archaeobotanical research. Ancient weed assemblages can inform us of growing conditions, harvesting practices, and crop processing post-harvest, to name but a few. This project provides us with a unique opportunity to study weed growth over a longer period of time. Archaeobotanical analysis will be carried out in collaboration with my supervisor Prof. Dorian Q. Fuller and Dr. Chris Stevens at UCL. At the moment, the weed assemblage study is focusing on identifying the natural seedbank at Butser Ancient Farm, with initial analysis showing legacy weeds of woad and oats – sown into the field a couple of years ago – and the rapeseeds from neighbouring fields.

The harvest this year will be our pilot study: an opportunity to improve on our research design and continue the project into the upcoming years. We believe this is an unique project not only to advance the study of lithics and ancient harvesting practices and their effects on weed assemblages, but also to potentially investigate the resilience of ancient farming practices in a changing climate.

Figure 3: weeds identified in the fields of spelt and barley during tending the fields on June 16, 2023. Photo: Anna den Hollander.

Equinox Viking Boat Burn 2023 tickets on sale this week!

It’s nearly that time of year! With the summer solstice passed, we’re looking ahead to the equinox — and our Viking fire festival that comes with it! Here’s everything you need to know about getting tickets this year, including all-new parking & travel options!

Tickets are releasing this week, so get ready! That’s Wednesday 28th, Thursday 29th, and Friday 30th June 2023.

If you’re not on our mailing list yet, make sure to sign up here →

This year, we’re bringing all-new parking and travel options to Equinox!

We do so love bringing folks to celebrate together at Butser, and our big fire festivals like Beltain and Equinox are some of our favourites. But they’re big festivals, and we’re a small site, so they really test our logistical ability to get everyone parked and into the festival.

That’s why we’re so excited to announce that this year, for Equinox Viking Boat Burn 2023, we have an exciting new parking & travel option! This year, you’ll have the option to park at a gorgeous local park, Queen Elizabeth Country Park, and choose how you’d like to get from there to us.

Lamp-lit Procession

We’re joined to Queen Elizabeth Country Park by a gorgeous 1.5km trail that gently winds through the South Downs to reach our door. Festival-goers who park at Queen Elizabeth Country Park will have the opportunity to join us on a procession to Butser, which will take around half an hour direct from the Visitor Centre at the park to the Equinox ticket gate. After the Boat Burn is complete and we’ve honoured the fallen warriors, we will be returning as a lamp-lit procession back to the car park at Queen Elizabeth to end your event. This brand-new pilgrimage will be an exciting addition to the Equinox Boat Burn and one we hope to repeat every year.

Shuttle Bus

We are also introducing a shuttle bus service for the first time! People who park at Queen Elizabeth Country Park will also have the option of booking a shuttle bus ticket, which will allow you to use this service to get to and from the festival. Buses will run regularly, and take about 5 minutes to get from Queen Elizabeth Country Park to Butser and the festival.

We hope these new options help more people than ever enjoy the magic of Equinox! Next on our wishlist: figuring out camping options… 👀 But that’s something for 2024!

From posthole to house – the experimental building process

As we prepare for our next Neolithic Building project, Experimental Archaeologist Therese Kearns describes the process and thinking behind preparing and researching for an experimental build here at Butser.

As we prepare for our next Neolithic Building project, Experimental Archaeologist Therese Kearns describes the process and thinking behind researching and preparing for an experimental build here at Butser.

Over the last fifty years, experimental building construction has been a key part of the work at Butser Ancient Farm. When the Butser Farm project started, the focus was mainly on the Iron Age and Romano-British periods; however, over the last two decades, the chronology of the Farm's building projects has been extended and now includes interpretations of structures from the Neolithic to the Anglo-Saxon periods. Our buildings are all based on archaeological ground plans, and one of our main challenges is translating a two-dimensional, partial ground plan into a three-dimensional structure.

Having the opportunity to 'reconstruct' prehistoric buildings is very special and we are always mindful of the impact that our interpretations might have. It's also a considerable investment and we take the journey from ground plan to finished building thoughtfully and carefully. The planning phase is one of the most critical parts of that journey, and each project we undertake comes with a different suite of evidence to work from.

We are currently planning our next project, which will focus on a late Neolithic building excavated on Wyke Down, near Cranbourne Chase in Dorset.

We were very excited when we first encountered the evidence for this structure because not only is there posthole evidence, but also a substantial amount of walling material and some very special pottery.

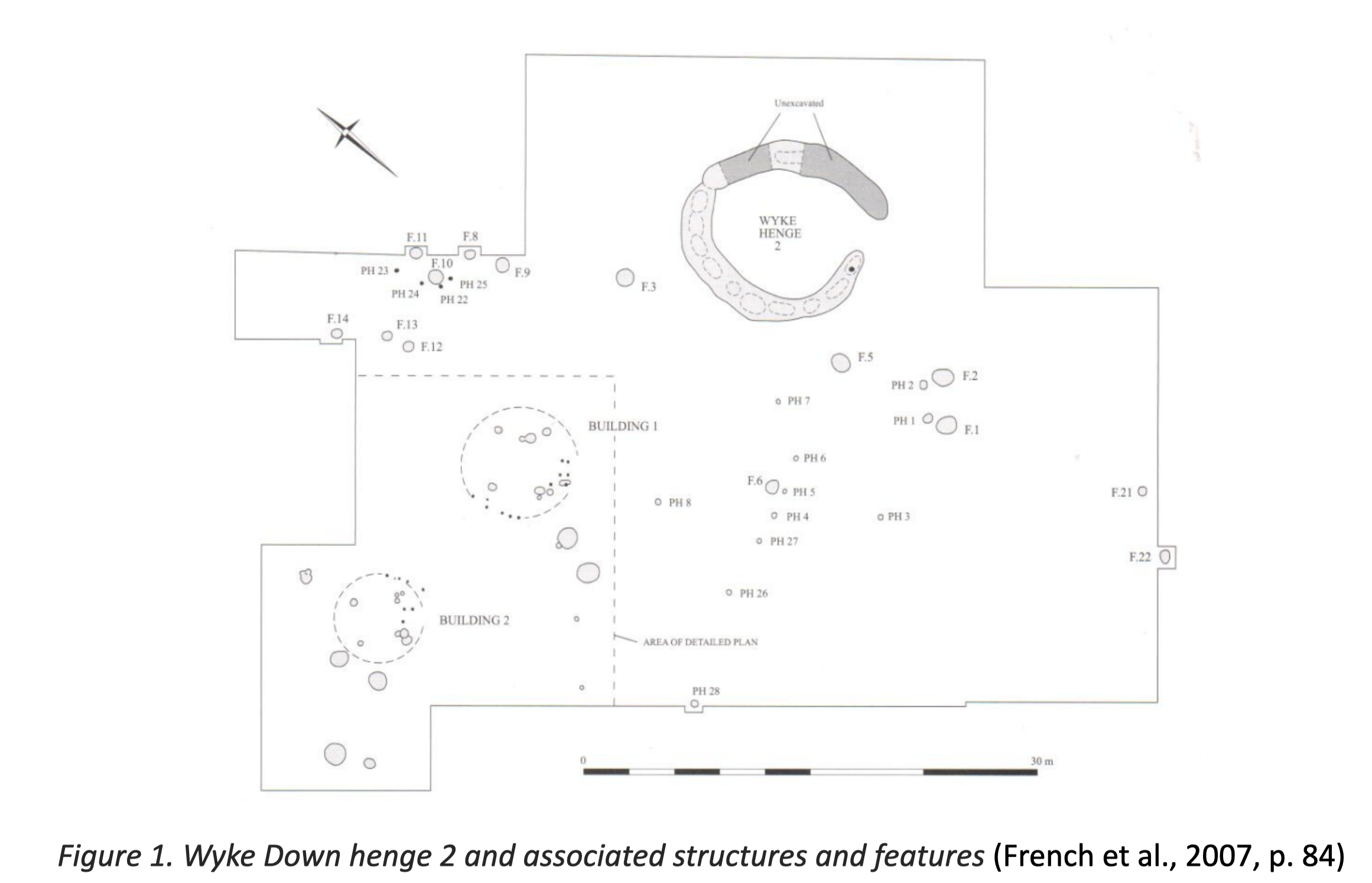

The site was excavated by archaeologist Martin Green, who has uncovered numerous important sites and monuments within the prehistoric Wessex landscape. At Wyke Down, evidence of two structures, 'Building 1' and 'Building 2', along with a henge monument – Wyke Henge 2 (fig. 1) were uncovered and it's likely that other features lie beyond the excavation area.

We will focus on 'building 1', the ground plan (fig. 2) of which includes an internal rectangular setting of four posts (postholes 12-15) covering an area of around 3.25 x 4 m. To the east, a smaller rectangle of four postholes suggests an entrance on the same alignment with a similar feature in building 2 and with the entrance to Wyke Henge 2. To the west an arc of five small postholes (36-40), may be part of an outer wall. The site sits on a slight east/west slope so we presume that much of the posthole evidence on the eastern side has been lost to the plough over time. When a circle is extrapolated from the centre of the large rectangle element to include the outer arc of posts and the entranceway, it suggests a structure of around 8m in diameter. However, the structure wasn't necessarily circular, so one of the challenges will be deciding what form it might have taken. To help us with this, we will look to contemporary evidence from other sites to help us build a better picture.

Charred material recovered from the structure's post pipes has been radiocarbon dated to 4203 +/- 33 BP – late Neolithic (French et al., 2007, p. 84), and more radiocarbon dating is currently underway.

A substantial amount of walling material was recovered from some of the postholes. This kind of evidence is rare from structures of this date and can tell us a lot about how the building might have looked and what it meant to the people who built and maintained it. Experts at the University of Cambridge have recently studied this material. Their results show that three different chalk-rich fabrics were in use, possibly in different parts of the structure. Some fragments retain the impressions of fine wattle likely to be either reed or willow (fig. 3), while others have incisions on the outer surface which may be part of a decoration. Several layers were built up over time, suggesting that care was taken to maintain the walls (French, 2023).

Finds from the postholes also included fragments of Grooved Ware pottery (fig. 4), a flat-bottomed form with grooved decoration. It is thought to have originated in Orkney and circulated throughout Britain and Ireland in the third millennium BC. The Grooved Ware phenomenon is associated with distinct forms of architecture, including timber circles and large four-post arrangements (Smyth, 2014, p. 318), similar to what we have at Wyke Down. This pottery evidence is vital for our interpretation as it allows us to compare with other 'Grooved Ware' sites, many of which appear in Ireland (see for example, Eogan & Roche, 1994).

Over the coming weeks, we will continue to research other sites of similar dates to gain the fullest possible picture of what this building might have looked like. One of the biggest challenges will be the roof, which is always speculative for structures of this period. We will also decide what materials to use and attempt to recreate the walling material using the results of the Cambridge analyses as our starting point.

The entire project will be documented on Butser Plus, so join us there to follow this exciting journey and discover what a late Neolithic' Grooved Ware' house might have looked like!

References

Eogan, G., & Roche, H. (1994). A Grooved Ware wooden structure at Knowth, Boyne Valley, Ireland. Antiquity, 68(259), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00046627

French, C. (2023). Wyke Down Site 2 (199): Micromorphological analyses of selected plaster/daub/cog samples from the late Neolithic settlement.

French, C., Lewis, H., Allen, M. J., Green, M., Scaife, R., & Gardiner, J. (2007). Prehistoric landscape development and human impact in the upper Allen valley, Cranbourne Chase, Dorset. McDonald Institute Monographs.

Smyth, J. (2014). Tides of Change? The House through the Irish Neolithic. In D. Hofmann & J. Smyth (Eds.), Tracking the Neolithic House in Europe: Sedentism, Architecture and Practice (pp. 301–327). One World Archaeology Springer.

A new shrine for the Roman Villa!

This month at Butser we’ve been delighted to receive a new addition to our Roman Villa - a beautiful Lararium, or Roman household shrine, made specifically for the Villa by artist Isabel Young from the Royal College of Art. Find out more about the new addition in our latest blog post.

This month at Butser we’ve been delighted to receive a new addition to our Roman Villa - a beautiful Lararium, or Roman household shrine, made specifically for the Villa and donated by artist Isabel Young from the Royal College of Art.

In the 20th anniversary year of our Villa it’s wonderful to see the Villa continue to grow and enable us to be able to expand the stories we can tell about Roman life in this unique space.

Find out more about the new addition below.

The new Lararium in place in the villa atrium

In ancient Roman dwellings a Lararium (a shrine to the household gods) would have been an important feature in every home and used in the practice of everyday private worship. Such artefacts found in the excavations of Pompeii have been a source of inspiration for Isabel Young, artist and Senior Tutor (Research) at the Royal College of Art, who has built a brand new Lararium for our beautiful Roman Villa. A free-standing aedicula now inhabits the mosaic room awaiting re-enactments and offerings in the interpretation of religious beliefs and ritual practices.

The Lararium has been designed with reference to the architecture of Butser’s Roman Villa and mirrors the wooden shutters, trusses, roof tiles and colour scheme of the villa building itself. While the theme is ancient, a combination of traditional and modern techniques has been used by Isabel to create the new shrine, including high tech laser cutting technology.

Paintings are an important part of Roman Lararium design, and a total of 8 paintings of snakes, as protective spirits of the house, decorate the surfaces of the shrine. The central figure of Ceres, goddess of harvest, and to whom the shrine is dedicated, presides over the altar as an important divinity for the farming community of Butser Ancient Farm.

A detail of one of the 8 snakes that adorn the Lararium

The Lararium has evolved from Isabel Young’s long-term exploration of the cultural dynamics of the house, vernacular architecture, ancient buildings, and the people who lived in them. We hope that this new addition to Butser can be used to expand on knowledge and understanding of relationships between the house, site, landscape, family, religion, ritual practices, and the pantheon of Roman deities.

Artist Isabel Young next to the new Lararium

A huge thank you to Isabel for creating this wonderful shrine for the villa!

Come and visit us from the 1st to the 4th June 2023 to meet Isabel and make a clay figurine to the roman household gods on a special drop-in workshop (included in your admission price) inspired by the Lararium.

Beltain Celtic Fire Festival 2023: Welcoming in the summer!

We celebrated Beltain Celtic Fire Festival with an afternoon and evening of music, mead, merriment, and of course, the burning of our 30ft wickerman. Here’s to good company and sunny days!

It’s Beltain! The ancient Celtic festival celebrated at the beginning of summer, and possibly even the origins of May Day. We celebrated this wonderful festival with an afternoon and evening of music, mead, merriment, and of course, the burning of our 30ft wickerman. Here’s to good company and sunny days!

This year’s wickerman was actually a wickerbeast, following the design of a phoenix to symbolise rebirth through fire — the same way our wickermen themselves live, die, and are reborn again each Beltain.

Thank you to everyone who joined us for this wonderful event! To everyone who made it out, to all our visitors and volunteers and supporters here, thank you for making things like this possible.

Stay tuned here for some of our favourite pictures from the event!

Relive the magic!

Watch the full commemorative video on Butser Plus for as little as £2.99!

Photos from Beltain Celtic Fire Festival 2023

With all our thanks

We are a small team from a small museum, and Beltain is an incredibly ambitious event for us to hold each year — one only made possible by an incredible number of wonderful people working very hard.

To all our staff and volunteers, thank you for your tireless work in preparing for and running this event! To the Friends of Butser Ancient Farm for your wonderful support, thank you.

To the Saxons of Herigeas Hundas, the Romans of Butser IX Legion, the ancient musicians of Here Be Flagons, to all the other reenactors and living history practitioners who helped bring our ancient farm to life, and to everyone who turned up in costume — thank you.

To the brilliant musical trio Polly Gone Wrong and the lovely band Tiger Moth, to the iconic Feckless who always gets us up and dancing, to the endlessly energetic Pentacle Drummers, and to the classic Ukes of Hazard, thank you for your wonderful performances.

To Jen Atkinson, Jo Dunbar, and Adrian Rooke, thank you for your wonderful talks on herbs, healing, elves, and the origins of Beltain. To Flying Iron, Steamship Circus, Ostara the Bubble Fairy, Mary Rose Royal George, Jez Smith, the Shanti Sisters, and Eva Greenslade, thank you for your work offering unique and incredible performances and experiences, from handfasting to axe throwing to archaeoacoustics.

To Neil Burridge, Joe the Smithy, Craig the Saxon Forager, Caroline and Tom of Pario Gallico, Fergus Milton, Jim Clift, and everyone from the Ancient Wessex Network, thank you for your wonderful demonstrations of ancient crafts and metalworking.

To Andrew Shorter, Jonathon Huet, Dawn Nelson, and Jason Buck, thank you for bringing such magic with your wonderful stories.

To Artscape, Granary Creative Arts Centre and HantsAstro for your interesting and interactive stalls, thank you. To Chalice Mead, Three Copse, the Whitelands Project, Langham Brewery, Bowman Ales, Mr Whiteheads, and Blackmoor Estate, thank you for supplying us — whether that’s with mead, local greenery, or our very own unique Beltain Cider!

To craftsfolk and traders the Wood Beyond the World, Pixie Made, Old Ways Candles, the Special Branch, Kevan Dyne, Minerva Crafts, Wesnet Services, Pipers Honey, Hare and Tabor, Finn’s Fire and Woodcarving, Woody Wonders Twig Pencils, Gina McAdam, Amongst the Gorse, Fantastical Kingdoms, Woolleymamma Leather, Willow and Crafts, and Gwen’s Garden — thank you!

To Crepe Britain, Matt with the hog roast, the Mobile Coffee Box, Earth’s Kitchen, and Sharon and Wendy of the Butser Bakes stand, thank you for all your work to feed everyone!

To Eleanor Sopwith, Alan Ridgley, Andrew Hayward, and Stanners Stanton, thank you for allowing us to use your stunning photos.

To friends unnamed but not forgotten, thank you.

And finally, to our supporters on Butser Plus, to our visitors, and to you 💚

Four of the Most Incredible Ancient Female Burials in Archaeology

We’re celebrating International Women’s Day! Let’s explore four of the most incredible ancient female burials in archaeology: from a tattooed princess to a Viking shieldmaiden, these women lived outstanding lives, and their graves can help us understand the world they came from.

Whenever we talk about ancient people and burials, it's really important that we remember there's much more to a person than the shape of their bones or a DNA readout — how they fit into society, what name they used, or how they thought of themselves are all still mysteries to us. We can’t even know for sure if the things they’re buried with belonged to or were important to them: that’s often how they make most sense to us, but the dead don’t bury themselves after all. And, as we'll see with some of these burials, mapping modern ideas about gender and society onto people from the ancient past is never a good idea.

This is a bit of a morbid topic, but this article contains no pictures of human remains, so you’re safe while you’re here.

With all that said, let's get right into exploring these four exceptional graves, and the lives of the people in them!

Selection of flint tools on display at Beltain 2022 // Image: William Mulryne

4. The Huntress of Wilamaya Patjxa

In 2018, archaeological excavations high in the Peruvian mountains uncovered a 9,000-year-old grave filled with so many hunting tools that archaeologists assumed they’d found a revered chieftain and master hunter. But as DNA testing soon showed, the grave belonged to a teenage girl.

In the end, there were six burials found at Wilamaya Patjxa, but this girl was the only one buried with hunting tools. And more than that — she was buried with so many tools, a whole Stone Age inventory of everything she would have needed to bring down big game and prepare its various parts. She had flint projectile points for arrows or a spear, knives and axes for butchery, scrapers and ocher for processing hide, and more. All in all, over 24 tools were found in her grave, grouped in such a way to suggest she might have had them in some kind of bag or container — a literal toolkit she could carry around with her.

This incredible find prompted researcher Randall Haas and his team to go back and look at other hunter graves in North and South America from this period. Women had been found with hunting tools before, which had often been explained in other ways — a flint projectile point can be useful for other things than just hunting. And it’s not unreasonable for researchers to assume that, in ancient hunter-gather societies, the division of labour would have been down gender lines: man the hunter, woman the gatherer. That’s how many modern hunter-gatherer societies work, after all.

But this find throws a wrench in that idea, and so do Haas’ findings: his team identified 27 graves from this period that include hunting tools for big game like ancient alpacas and deer. 11 of those belonged to women. Far from hunting being exclusively for men, Haas now believes as many as 30-50% of big game hunters could have been women, meaning the division of labour for hunter-gatherers may have been much more gender neutral than people assumed.

Recreation of the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman headdress at Beltain 2022 // Image: Harvey Mills

3. the shaman of Bad Dürrenberg

Discovered by archaeologists in Germany in 1934, this grave was immediately clear to be something really special. The 8,500-year-old body was surrounded by more than 150 bones and artefacts, and the Nazis, in power by that time, fell about themselves trying to claim the grave belonged to an ancient Aryan man. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

The body belonged to the woman we now call the Shaman of Bad Dürrenberg, and she wasn’t alone — she was also buried with a baby boy, assumed to be her own child, although recent research throws that into doubt. The two people were buried in a red clay reserved for important and respected individuals, and the woman was quickly identified as a likely spiritual leader. It seemed she had some kind of headdress made of deer antlers and pierced boar teeth pendants, and the items around her were made from many other bones, even from cranes and tortoises.

Study into the Shaman’s own bones has revealed she had scoliosis, and may have suffered from various neurological conditions as a result of her bone structure — involuntary eye or limb movement, head and neck pain, sensations of crawling skin, and even hallucinations. In a culture that may have practiced shamanism, these could have been interpreted by her or her people as spiritual trances or visions. It’s even possible she may have learnt to control some of her symptoms and induce an altered state at will.

In their 2022 book, archaeologists Harald Meller and Kai Michel revealed that the Nazis were even more wrong in their assumptions. Not only was the Shaman a woman, and a woman whose experiences with disability may have elevated her as a spiritual leader, but like many early humans the Shaman of Bad Dürrenberg was also dark-skinned.

Butser roundhouses enveloped in winter fog // Image: Butser Ancient Farm

2. The Siberian Ice Maiden

In 1993, a team of archaeologists under Natalia Polosmak made an incredible discovery in the Eurasian Steppes of Siberia. Deep in a burial mound, suspended by thousands of years of ice and permafrost, was a 2,500-year-old mummy.

The Siberian Ice Maiden, as she’s come to be known, was given a lavish burial. She was dressed in brightly-coloured silks and an incredible 3-foot tall headdress, with a polished mirror and makeup supplies near to hand. Leather deer were appliquéd onto her casket, and her headdress was decorated with golden cats. Around her was placed a feast — and, thanks to the ice, parts of the food were preserved even thousands of years later: deer meat, a drink for the afterlife, and something that might have been yoghurt.

The most incredible part of this archaeological discovery, though, is the woman herself. The ice kept her in such a good state that you can still see the tattoo on her shoulder — a leaping deer. The incredible state of her preservation also meant that, in 2014, researchers Andrey Letyagin and Andrey Savelov could conduct an MRI scan on the mummy. And their findings are really significant: she had chronic pain.

The woman was dying of breast cancer, and had suffered a recent fall (from her horse, perhaps) that fractured her skull. Together, this knowledge sheds new light on another item she was buried with: a little container of cannabis, possibly taken for pain relief.

Thanks to the way she was preserved, we know so much about the Siberian Ice Maiden. It’s not hard to imagine this young woman, in her 20s when she died. She wore eyeliner, rode horses, got tattoos, fought cancer, took painkillers, and commanded intense respect from her people.

Saxon reenactor with Herigeas Hundas at the Equinox Viking Boat Burn 2022 // Image: Alan Ridgley

1. the birka viking warrior

In 1878, archaeologist Hjalmar Stolpe uncovered in Sweden one of the most remarkable graves of a Viking warrior ever found. It was a 10th Century grave of the ultimate Viking warrior, and, as was proved in 2017, it was the grave of a woman.

The Birka Viking Warrior was a trained fighter. Rather than the two or three weapons most warriors were buried with, she had a full set of battle equipment covering a variety of fighting styles — sword and shield, bow and armour-piercing arrows, horses for mounted combat, axes for hand-to-hand fighting, a spear for range… More than that, her weapons were battle-scarred. These weren’t ceremonial or symbolic, they were real equipment for a professional fighter.

She wasn’t just buried with weapons, either — her clothing and other grave goods, including a tactical board game hnefltafl, suggest she was affluent and respected, and may even have been a commander with her own warband. Textiles experts analysing her clothing have argued that she was of such a high status that she may have answered directly to a royal military leader.

In the 10th Century, Birka was a major Viking trading post and the first real city in Sweden, and it had a hillfort with a military garrison for defense. When she died, the Viking warrior was buried outside the gate of the hillfort, beside two other graves containing a lot of weaponry, so it seems likely she was a professional warrior tasked with the defense of one of the Viking world’s greatest trade centres. If she could do it, how many more Viking women warriors could we be missing?

Archaeology is always an exercise in interpretation — we don’t know for sure how these people lived, or if our understanding of their graves is right. But burials give us some of the best snapshots into the past, and help us understand what was important to a people and their culture.

These four burials give us a glimpse into ancient worlds where women were hunters, fighters, and spiritual leaders, and remind us that you can’t make assumptions when you look at the ancient past!

First Time Thatching

Sam Hall, a member of our education and public engagement team, reflects on his experiences learning to thatch on our new Danebury CS20 Iron Age Roundhouse.

Sam Hall is a dedicated member of our education and public engagement team here at the farm, but as with all jobs at Butser there is always the opportunity to learn a new skill and get stuck in to one of the many projects taking place at the farm.

Here Sam reflects on his experience learning to thatch and helping out on the construction of our latest Iron Age Roundhouse- Danebury CS20.

Thanks Sam!

Butser Ancient Farm resonates with a long-lost past and all its traditions in many ways. From its own history of extensive archaeological research to the experimental structures which exist on site, the commitment of the Farm to expanding our own understanding of British prehistory (including, of course, Roman and beyond!) is clear for all to see.

Something else at the Farm which resonates with a deep-rooted practice of human society is the idea of skill-sharing. In many ways this is of course practiced today, although for entirely different reasons: usually it is in working multiple apps, devices, and machines. But what about when the machines disappear? The skill-sharing at the Farm instead focuses on traditional hand-crafts that are both physically and mentally demanding, in which you, and the small team with whom you work, become the determining agents as to whether it goes particularly well or not so much (no pressure!).

Luckily, in my first week thatching, the pressure was almost nonexistent, as I was working under the supervision of Paul Corrie. This meant that not only could I take the time to focus on all the aspects of thatching itself, but also that I could have that time to assimilate and learn the skills I would need to pick up. All of this is necessary to ensure that the reed roof of the new Iron Age roundhouse actually stays on - wouldn’t that be a good start?

Sam’s thatching work on Danebury CS20 Roundhouse

Here you can clearly see the older darker reused thatch and newer thatch on top.

Mistakes being a key part of any human labour, the idea of having sufficient time to actually learn multiple aspects of any one craft is what makes skill-sharing such a success. There is, unlike many parts of life today, no time to rush; doing so is likely to lead to more costly, time-consuming, and labour-intensive problems to fix.

Learning in this way makes historical sense too. It is one thing to live as part of a society, like we do today, which has a hyper-abundance of products. What of those prehistoric peoples who, to get anything at all, had to work hard at each step? The hazel rods, for example, making up multiple purlin rings around the heavy timber roof, would not have come to those people pre-cut and shaped already. Instead, they would have their starting point at the tree itself, to which they would have to take their axe (again, the result of a long process of iron ore extraction, smelting, forging, and so on) before carrying the timber back to wherever the new house was being built. Each step of the way was a learning curve for those people, with the time and energy invested being more precious than money; no machines could step in to replace their effort and dramatically reduce the time involved; it was vital, therefore, not to waste resources.

So, although my very first week learning to thatch a roundhouse roof covered a small portion of the third lift (or “level” of thatch), it provided plenty of opportunity to resonate a fraction more with how those before us had to go about things. Down to the seemingly minute details - for example, are the reeds spread thin enough? - and the unforgiving nature of thatch when tied on properly - there is little movement to push through, although that is needed to get the next bundle tied securely to the beam behind - the feeling of scratched, cold hands makes prehistory and its people feel incredibly close.

On top of that, the opportunity to begin this learning journey adds an enormous amount of value to the educational side of work at the Farm. Enabling the skills experienced and learned first-hand to be communicated with eager students puts a priceless value on the past and encapsulates what it means to bring to life practices and skills which are slowly being lost.

Danbury CS20 Roundhouse being thatched, February 2023

Firing a Roman Kiln

Previously in our blog we heard from Professor Bill Sillar - Professor of Archaeology and Technology in Society at UCL Institute of Archaeology about the Roman Kiln UCL built at the farm. Below Bill describes the process of firing the Kiln for the first time during UCL’s ‘Archaeotech’ experimental archaeology course.

Previously in our blog we heard from Professor Bill Sillar - Professor of Archaeology and Technology in Society at UCL Institute of Archaeology, about the Roman Kiln UCL built at the farm. Below Bill describes the process of firing the Kiln for the first time during UCL’s ‘Archaeotech’ experimental archaeology course.

In September 2022 the UCL team returned to fire up the replica Roman Kiln they built in April.

Constructing the Roman kiln in April 2022

The kiln, based on an early second-century Roman kiln on the banks of the River Medway, originally excavated in 1975 by the Upchurch Archaeology Research Group (UARG). By September our replica kiln was dry to the touch, but still had a lot of moisture in the clay, so we started with a small fire at the base of the chamber to dry out and warm the kiln structure. We then placed our pre-prepared pedestals and kiln bars and continued to heat the structure.

A couple of the kiln bars broke, probably as we heated them up too quickly to release the moisture in the clay. We had made a few pots on the kick wheel we brought from Fishbourne Roman Palace, but, as with the original kiln assemblage, we made the majority of our pottery using hand building techniques, including a range of jars of similar sizes to those found in the excavated kiln.

The first firing of the kiln

So, we loaded the kiln placing the jars and other pots mouth downwards, we put two layers of pottery with a mixture of vessels. We continued to slowly heat the kiln. For fuel we were using coppiced wood from fences and structures that had been dismantled at Butser, this was predominately hazel that was aged and fairly dry, so a very suitable fuel to use in the restricted opening of the kiln flue. As the pottery began to heat up we placed a covering of pottery sherds (including some fragments of original Roman tiles) over the kiln load. (An interesting question is whether some of the pottery excavated at the original Medway kiln was being used as a sherd covering for the firing.)

The firing continues into the night

The results of the first firing

We kept the firing going into the night reaching a temperature of around 860 centigrade, and then left it to cool before unloading the following morning. This first firing was fairly successful with only 3 vessels completely shattered, but the pottery was slightly underfired and some large vessels had small cracks or chips, which were probably a result of production and handling faults. About 20% of vessels were partially reduced/carbonised as a result of poor circulation of air/oxygen during the firing.

The second firing of the kiln

Results of the second firing

A second firing was more successful reaching a temperature of 960 degrees, but again with about 20% of the pottery partially reduced/carbonised. We now intend to undertake further analysis of the original assemblage from the Medway kiln to consider how our improved understanding of the kiln might help our interpretation and we hope to undertake further firings to assess how different fuels and methods of covering influence the firing conditions.

Thank you very much to Bill and all the staff and students from UCL and Archaeology South East for building and firing this fantastic kiln here at Butser . We are looking forward to the next experiments!

Blog archive

- December 2025 2

- November 2025 2

- September 2025 1

- April 2025 2

- February 2025 1

- January 2025 1

- November 2024 2

- August 2024 1

- July 2024 2

- May 2024 1

- November 2023 1

- October 2023 1

- September 2023 1

- August 2023 1

- July 2023 1

- June 2023 2

- May 2023 2

- March 2023 1

- February 2023 1

- December 2022 1

- October 2022 1

- August 2022 2

- April 2022 1

- March 2022 2

- February 2022 1

- January 2022 1

- December 2021 2

- November 2021 3

- October 2021 2

- September 2021 5

- August 2021 2

- July 2021 3

- June 2021 3

- May 2021 2

- April 2021 4

- March 2021 1

- November 2020 1

- October 2020 2

- August 2020 1

- March 2020 4

- February 2020 4

- January 2020 3

- December 2019 3

- November 2019 1

- October 2019 1

- September 2019 1

- August 2019 1

- July 2019 6

- June 2019 3

- April 2019 2

- March 2019 3

- February 2019 2

- January 2019 1

- November 2018 1

- October 2018 2

- September 2018 3

- August 2018 4

- July 2018 2

- June 2018 2

- May 2018 2

- March 2018 6

- February 2018 1

- October 2017 1

- September 2017 5

- August 2017 4

- July 2017 3

- June 2017 1

- May 2017 1

- April 2017 3

- March 2017 2

- February 2017 3

- January 2017 1

- December 2016 2

- November 2016 1

- September 2016 1

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- June 2016 3

- May 2016 2

- April 2016 1

- March 2016 2

- February 2016 1

- January 2016 3

- December 2015 2

- November 2015 1

- October 2015 1

- September 2015 2

- August 2015 1

- July 2015 2

- June 2015 2

- May 2015 3