A guest post by Dom Price, Species Recovery Trust, on the experiments at Butser Ancient Farm.

Ancient crops, strange fungus and witchcraft.

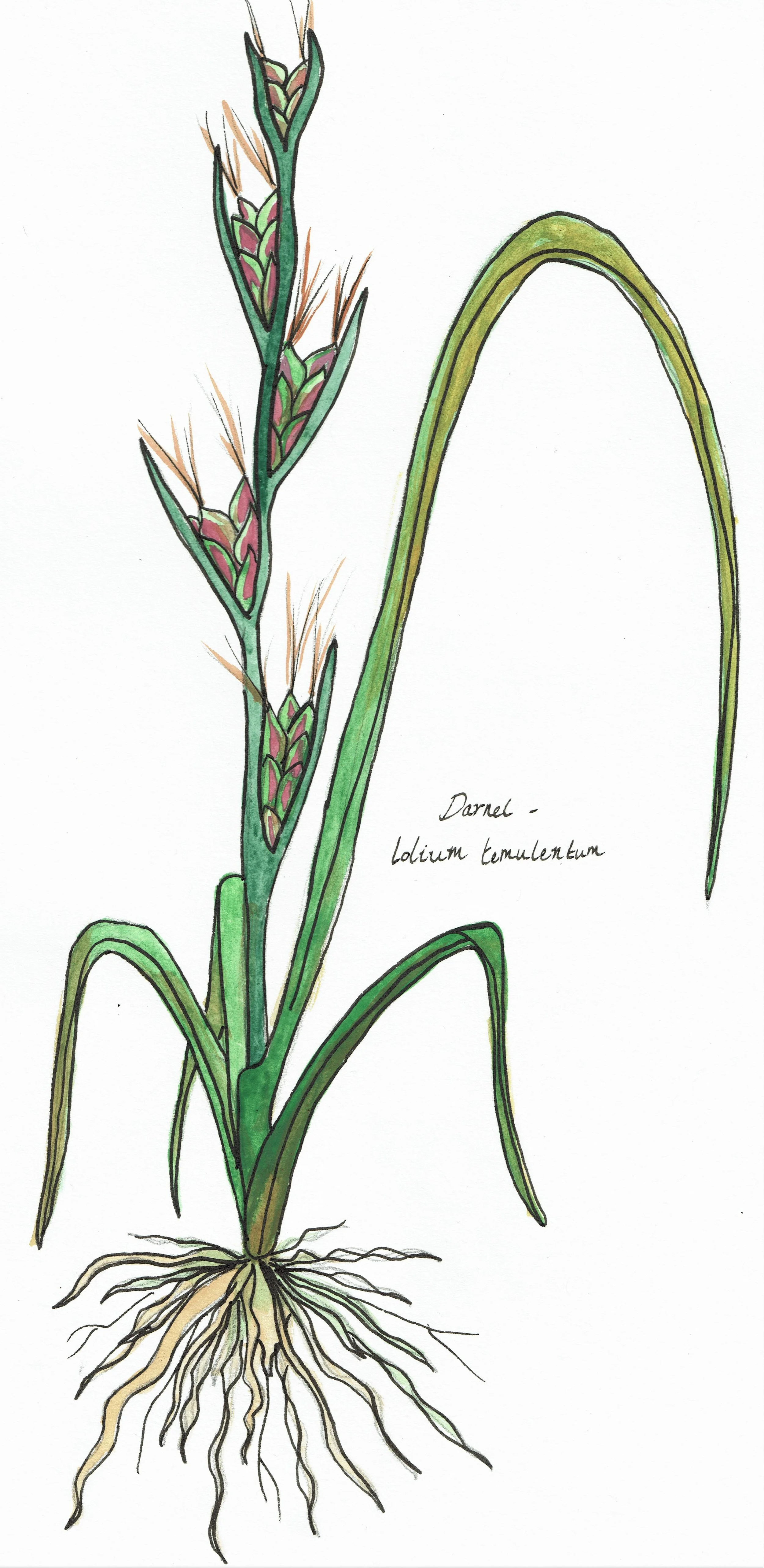

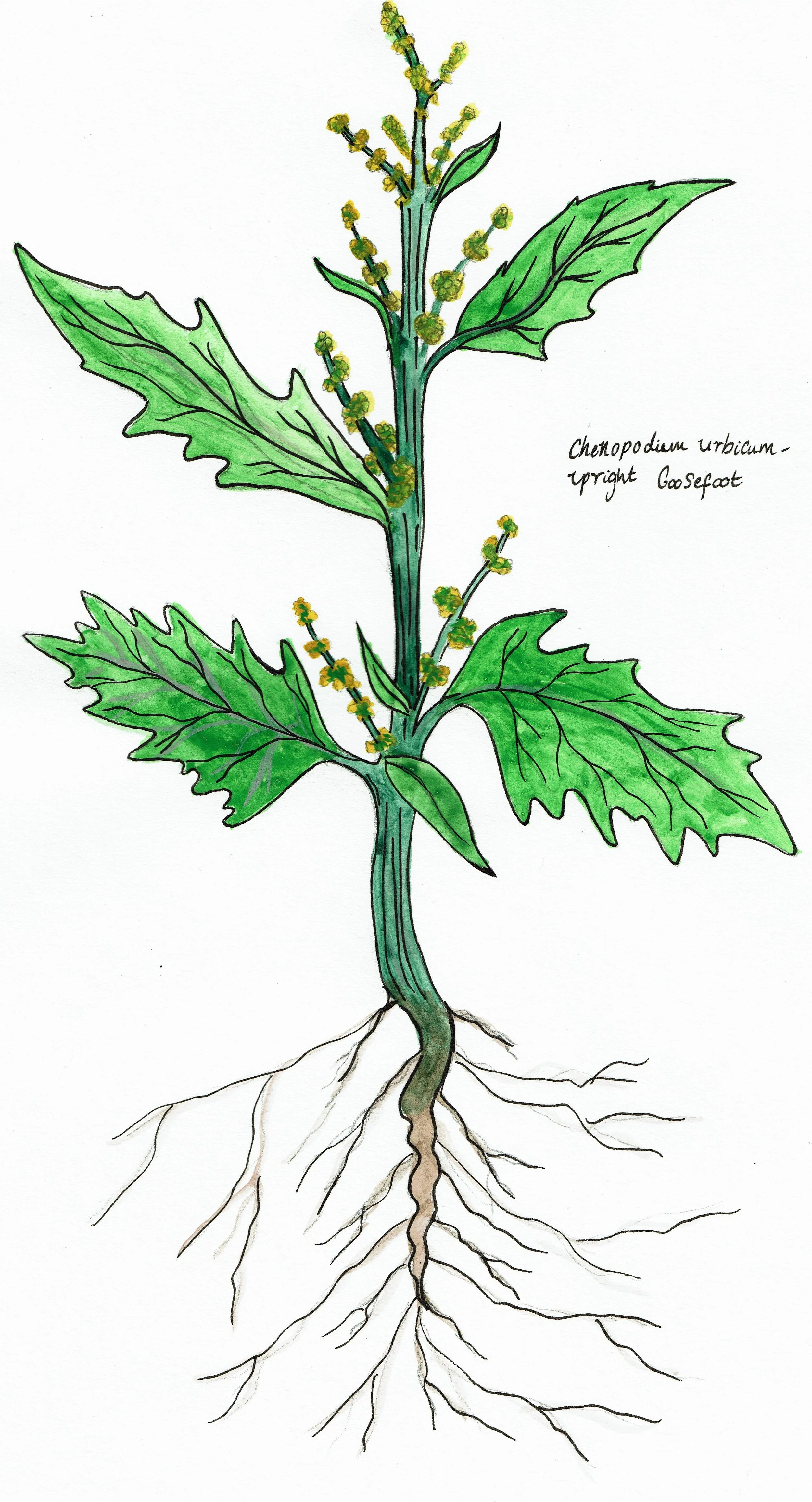

Butser ancient farm is a key site forming part of a project to re-introduce two species of now extinct plants. Darnel and upright goosefoot were both a relatively common site in ancient farming systems before the introduction of modern agriculture, including the widespread use of herbicide and improvements in seed cleaning technology which allowed all ‘weed’ species to be removed before seeds were re-sown.

Both of these plants vanished from mainland Britain over two decades ago, and Darnel is now hanging on a knife edge on the Arran Isles off the west coast of Ireland. Having managed to obtain seeds for both the species, we first started growth trials at Butser in 2015. During this time we’ve learnt a lot more about the ecology and life-cycle of both plants, but also had a chance to observe them within a low-level arable system.

Both species have proven extremely challenging to grow; we lost nearly all the plants in the heat wave of 2018, and goosefoot in particular, while good at germinating, seems reluctant to form any decent quantity of mature plants.

In 2019 we will be growing Darnel in amongst a nurse crop, to replicate the way it used to occur in mediaeval Europe. This will allow us to study in more detail the way it interacts with the crop also give us a glimpse of the habitat type which our ancient ancestors would have been much more familiar with.

In its peak Darnel was a serious contaminant of crops in medieval times, and it is believed that many phrases, such as ’taking the bad with the good’ originate from this mix of crop plants. Darnel was a particularly problematic plant as its presence often led to infestation with the Ergot fungus. When the infected grain entered the food chain this led to outbreaks of ergotism. The early phases of this illness were characterized by wild hallucinations and seeing of visions, which led to an entire folklore around the disease with rumours of witchcraft and demonic possession.

On an agricultural level, the growing conditions were right for ergot to flourish — a wet season in 1691 would have been perfect for ergot to spread on the rye. In addition, Salemites were unlikely to have known what ergot was, and Caporael found later letters that showed ergot was a significant problem in the area. Recent research looking at weather patterns in Massachusetts have led scientists to believe an outbreak of ergotism may have been behind the Salem witch trials.

The Ergot fungus is still very common in the wild, and very rarely enters the food system these days.

Dom Price , Species Recovery Trust

Useful links - https://www.vox.com/2015/10/29/9620542/salem-witch-trials-ergotism- http://speciesrecoverytrust.org.uk/